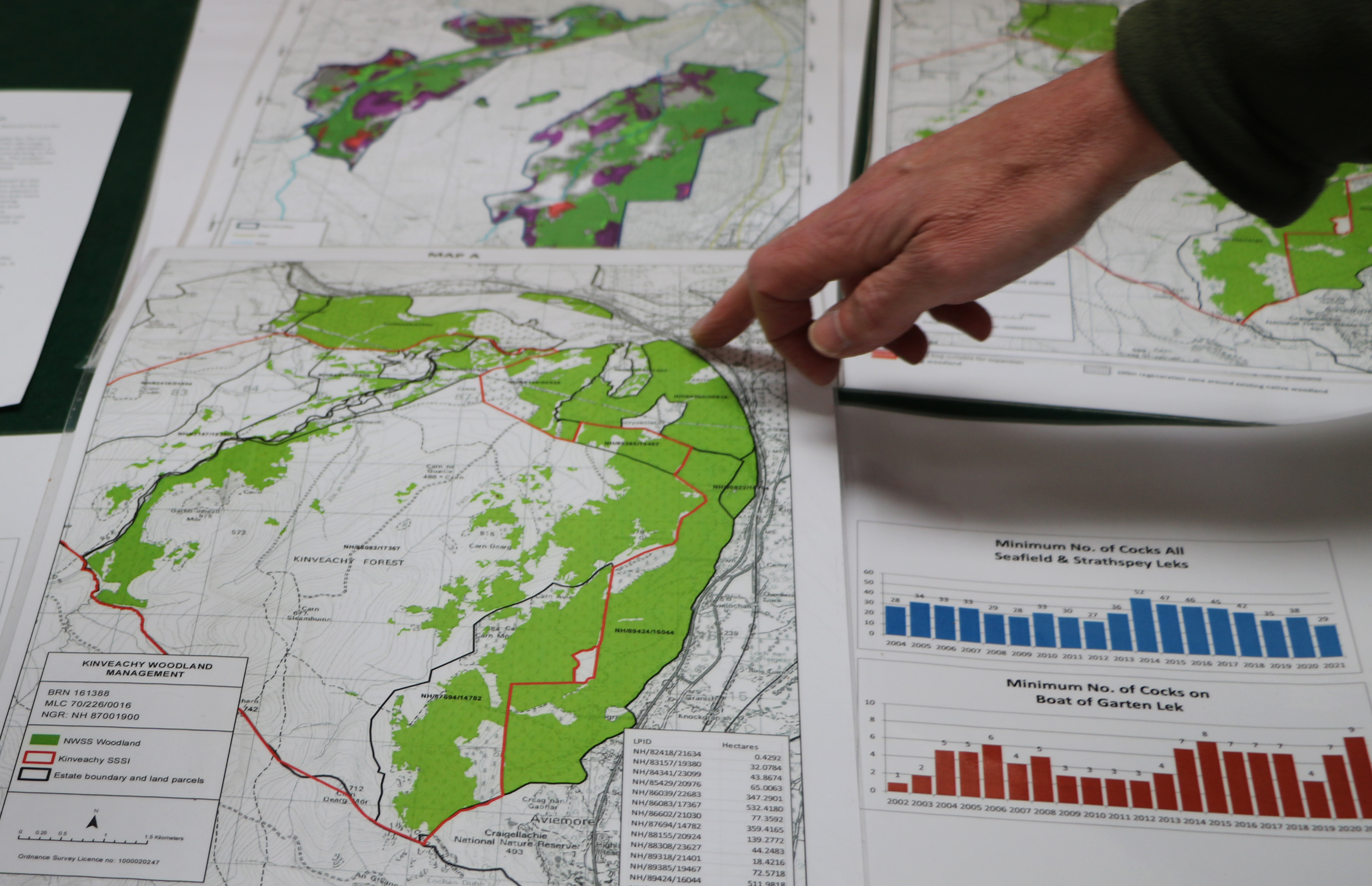

Bright sunshine floods the strath with light, but the chill air of spring makes me glad I’ve packed my good coat as we arrive at Kinveachy Forest and meet our guides for the day, Will Anderson and Ewan Archer, stewards of the Seafield and Strathspey Estates. On a day like today their office, the 23,000ha of these Highland Estates, of which Kinveachy forms just over a fifth, comprising ancient Caledonian pinewoods, forest plantations, heather moors and a section of the Dunlain river, spawning tributary of the Spey, surely can’t be bettered. But managing this landscape year-round, through all weathers, and often late into the night can’t be easy. And this land, so altered over centuries by human hand, and now devoid of apex predators, is vulnerable to change.

The Strathspey Estate is home to a diversity of wildlife, ranging from red grouse and other upland species such as skylark, curlew, golden plover, lapwing, and mountain hare to a variety of species of birds of prey including buzzard, golden eagle, white-tailed sea eagle, hen harrier, hobby, kestrel, merlin, peregrine falcon, red kite and sparrow hawks. Remnants of natural forest, most recently deforested primarily for the war effort and dominated by Scots pine, support species that rely heavily on this habitat, including Scottish crossbills, black grouse, and Capercaillie.

Much of the Estate falls within the Cairngorms National Park boundary, and more than 14,200 acres have been designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Large areas are also designated as Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and Special Areas of Conservation (SACs). These designations have caused management priorities to shift, as evidenced by the grey stone lodge we pass on our way into the forest, once used to house visiting hunters is undergoing renovation to be put to another use, and the delivery of specific and measured biodiversity benefits is now high on the agenda.

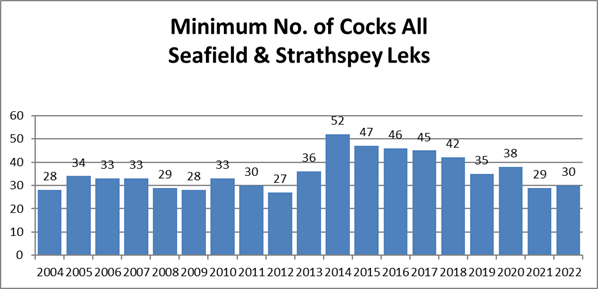

One of the species most under threat is the Capercaillie, a large woodland grouse. Reintroduced in the 19th century after becoming extinct in Scotland in the 18th century, it is now again at serious risk of disappearing from our woodlands. Strathspey has the largest concentration of Leks (Capercaille breeding displays) in Scotland, but the population is contracting to this last stronghold. Concurring with the recent NatureScot Scientific Advisory Committee Review of Capercaillie Conservation and Management, Will and Ewan identify predation and human disturbance as key factors. In the 24hrs prior to our visit, a Capercaillie cock was killed by a fox and a lek deliberately disturbed by a member of the public (who was charged by the Police). But with much of UK wildlife under threat, and many species protected accordingly, this can see one or more threatened species fighting it out with another for survival. Take pine martens who, like Capercaillie, are a protected species in the UK - they are thriving in this part of Scotland but this is thanks in-part to a diet of Capercaillie eggs! As other areas of the UK boost their depleted pine marten populations via translocations, perhaps in time some of the estate’s martens will be helped on their way to more southerly climes.

(Refs: RSPB; Scottish Wildlife Trust)

In the meantime, the estate team do their best to improve the habitat they have, encourage the public to avoid lekking birds and to monitor the situation – recording not only quantitative data but also their observations on the birds’ behaviour and preferences. Will explains that in one nearby lek, which is worryingly close to human activity, Capercaillie numbers are stable or even increasing. Surprisingly this lek, like many others, is to be found in a plantation rather than a natural forest, however, its resilience may be due in part to the undulating ground in the area, which provides excellent hiding places for the birds. Thinning has improved habitat structure, providing a mix of open canopy areas, to allow growth of the understory, especially blaeberry, needed to provide the insect diet of the chicks, and dense areas that provide cover. Indeed, enabling wildlife to access the whole range of habitats it requires to successfully complete its life cycle, is something Will and Ewan agree is key, the scale of the estate and the mosaic of landscapes it provides, allows for flexibility and a landscape approach to its management. Some interventions are a more experimental.

Like many birds, Capercaillie need to consume gastroliths – small stones to help them to digest their food. And so, Ewan has begun placing piles of quartz grit in safe locations for the Capercaillie to discourage them from picking up grit from certain well used tracks, where they are more vulnerable to disturbance by people. Some birds, however, seem to have missed the memo. Ewan brings his vehicle to a stop in the forest, sun streams through the pines, but the resident we were hoping to meet is yet to make an appearance – a familiar face to Ewan, one Capercaillie cock has taken quite a shine to the vehicle. But he’s not here to meet us – at this time of the year he probably has better things to do with his afternoons!

Having held FSC forest management certification for more than 20 years via the Tillhill group scheme, the stewards of this forest view its requirements as just another part of their day-to-day management. The biggest impact has been on record keeping, they agree, helping to ensure continuity between different forest managers. The auditing process is useful in providing new and different perspectives on issues and practices and encourages managers to question their approaches. This continual review and readjustment of monitored objectives, and the ability to meet demand for certified timber from mills are key benefits of certification for the estates, which comprise 10,800 certified hectares and both estates produce a combined 25,000 tonnes of timber each year.

Once prized predominantly for its hunting potential, much of the estate’s work still focuses on deer management, systematically reducing and maintaining deer numbers, in the absence of apex predators, in order to support natural forest regeneration and strike a biodiverse balance. The estate values the deer as an important part of the habitat and managing it at an appropriate level is challenging but vital to provide a range of benefits. What’s wrong with too many deer? Mainly, browsing – eating up the fresh young shoots of saplings – which, can lead trees to be damaged, deformed or killed, hampering growth and regeneration.

Deer fencing can be used to keep them out of vulnerable areas, but it’s a problem for Capercaillie, who can be killed if they fly into it - every action, has an impact, everything is linked. Instead, the use of fencing is minimised and the fencing that is used made more apparent to the birds by marking with wooden droppers, a process that is ongoing to replace the old plastic netting. The deer are constantly moved around the estate, much as they would be by a natural predator, to reduce damage from browsing. Or at least, almost constantly – in harsh winters, when they seek refuge in woodland areas, they are allowed to rest to ensure their welfare and have, in some years, been fed to keep them away from sensitive regeneration. Overall, numbers are kept low, with just 2-5 deer per km. Those that are shot must be quickly returned to the larder for processing. The “grallochs” (offal) are also removed from the hill – too much carrion again could upset the balance, providing overly accessible and rapidly decaying food and attracting and benefitting predators. To this end, the estate has on-site facilities, enabling it to make an income from the sale of venison, another healthy and sustainable product from managed woodlands.

As we near the end of our tour and the edge of the forest, bisected as it is by the A9, the predominant tree species changes – the Scots Pine taking a backseat to the slowly leafing birch and aspen, Ewan points out one large stand of aspen which is actually not a number of separate trees but one. The aspen is actually an interconnected clone – one being, or rather two, divided as it was by the construction of the A road, and somehow underlining the day’s recurring themes of natural connection and human intervention – and the decisions we must make as we attempt to re-balance the ecosystem scales, replacing the items removed by the actions of our ancestors.

This article was written by Tallulah Chapman, FSC UK Communication Manager.